Today’s hymn is Fintan O’Carroll’s “Alleluia, Father we praise you as Lord”. Both the chorus and verses have memories for me.

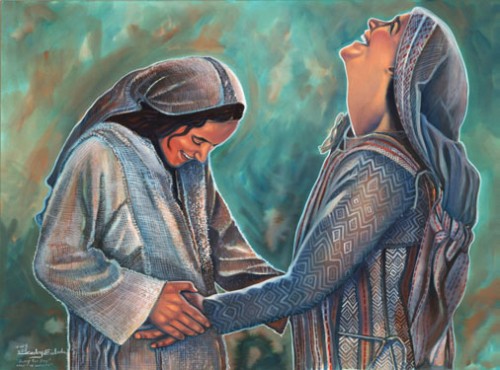

The chorus, or perhaps antiphon (congregational response) is the technically correct term, is a setting of the word Alleluia! sung four times and on its own is known as the “Celtic alleluia”. It is used in several churches of a more Catholic style, including one where I sometimes worshipped in London (St Luke’s Charlton), as the ‘greeting of the Gospel’. This is a tradition whereby the Gospel book is processed from the altar into the middle of the congregation to be read, as a symbol of God’s word coming among his people. By singing “alleluia” as the book arrives, we are praising God for coming among us. This is a reminder that when we talk of the “word of God” we mean not just the Bible, important though that is, but the very nature of God which is to communicate truth and love to the world he has created, most importantly when he was incarnated in Jesus Christ to whom the Gospel accounts bear witness.

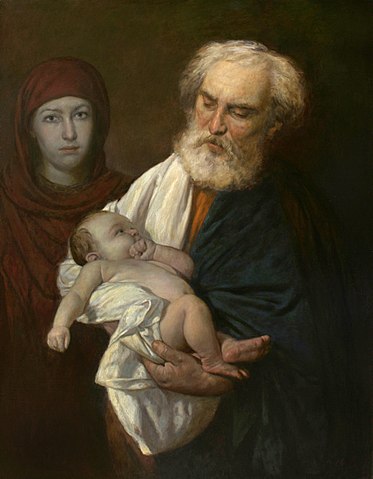

As is noted in the hymn book, the verses are a setting of “Te Deum”, an ancient hymn of the Latin church. In it, everything created is urged to give praise to God. In the original this starts with the angels, cherubim and seraphim (the spirits surrounding God’s throne and his messengers). They praise him with the song “Holy, Holy, Holy” which is also sung at the Communion / Mass, although in this hymn setting it is “we” who praise God the Father in this way. They are followed by “the glorious company of apostles, the noble fellowship of prophets, the white-robed army of martyrs” – those who founded the Church and those who at a time of persecution were honoured for having given their lives for Christ. These praise God as Father, Son and Holy Spirit. After that comes the song of the whole church in praise of Jesus as both man and God. The final section reminds us that he will come again as judge, although that isn’t explicit in the hymn setting.

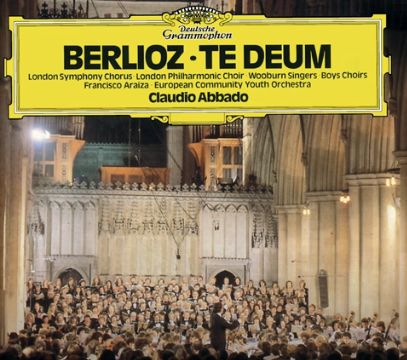

The memory for me here is from my schooldays. I wasn’t a regular member of the school choir, but when it came to plans to perform Berlioz’s setting of Te Deum, the call went out for additional singers for a work that demands a large choir. Since I enjoyed singing hymns in assembly, I volunteered. The experience of rehearsing this great choral work helped draw me into both a love of classical music and a personal faith in Christ over the next few years. Sadly, I fell ill just before the performance and didn’t get the experience of singing it to an audience. But worship doesn’t need an audience, for in worship – alone or in a massed choir – we are praising God himself.