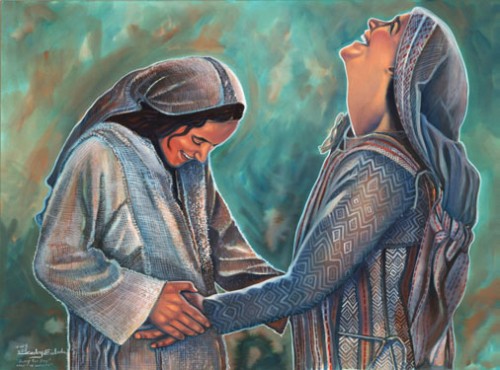

Jump For Joy by Corby Eisbacher

Today’s hymn, “My soul proclaims your mighty deeds”, is Owen Alstott’s verse-and-chorus setting of the Magnificat (Mary’s song), and the words are familiar to anyone who knows Luke’s gospel, so there’s not much to say about them, except this: Magnificat is traditionally associated with Evening Prayer in the Church of England but I’ve sometimes wondered why it’s not associated with than morning prayer instead, as unlike the Nunc Dimittis (the song of an old man about to die in contentment) it’s such a celebratory, hopeful song, sung by a young woman during her first pregnancy. Surely it goes better in the morning when the promise of the new day lies ahead? So I sang it this morning although I’m only writing these notes in the evening.

I used to know all these things without having to look them up, but age is obviously telling on me! Jasper & Bradshaw (“A companion to the ASB 1980”, p126) says about Magnificat: “Although used in the Morning Office in the East and in the Gallican churches, it was St Benedict who gave it its position as the Gospel Canticle* at Vespers, and it has retained its position there ever since.” Benedict (and others) drew up schemes of seven services** every day (because Psalm 119:164 says “Seven times a day will I praise you”), but by the time Cranmer was revising the monastic practices before producing the 1549 Prayer Book, there was already a trend to saying these services in two blocks, one at the beginning of the day and one at the end (p90), and Cranmer basically combined three of them (Matins, Lauds, Prime) into Morning Prayer and two (Vespers and Compline) into Evening Prayer, so that’s how Magnificat got its place. In the modern CW DP services a bit of a feature has been made of this aspect: canticles* based on the OT are set for Morning Prayer, and canticles based on the NT are set for Evening Prayer. I agree with Stephen that it feels odd.

Jasper & Bradshaw also point out that the song is “a mosaic of OT phrases, e.g. 1 Sam 2:7, 2 Sam 22:51, Ps 89:11, 98:3, Job 5:11, 12:19, Is 41:8, Mic 7:20.”

I think a lot of what I wrote about “Bless the Lord, my soul” applies to this song also (and to a fair number of others in the book, for example “Holy Spirit, come to us”). I would far rather see writers make a determined attempt to cast the thinking of the biblical text into metrical stanzas that rhyme and scan (and I’ve written a few such attempts myself). And I found the tune’s bass line a little unconvincing: surely it ought to move in contrary motion to the melody more often, and avoid the parallel fifths in bar 6 (“its joy”) of the chorus and parallel octaves at the end (“your name”) of the verse? But everyone to his/her own taste, and I don’t mind singing this one (and I sang it in the morning too!).

– – – – –

* the word “canticle” just means a passage of scripture which is used as a song.

** Matins, Laud, Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers and Compline. (You’ll see there are actually 8, the reason is that Ps 119 also says “At midnight I rise to praise you” (v62), so the monks slipped in an extra which was originally called “Vigils”, but its end drifted towards sunrise so it got renamed Matins). Lauds is at daybreak, Prime, Terce, Sext and None are to be used at the 1st, 3rd, 6th and 9th hours (their names are these numbers), Vespers at sunset, and Compline last thing before bed. (The twelve “hours” are divisions of daylight, so they are shorter in winter and longer in summer.)