(one of the last organs built by the late Kenneth Tickell in 2014)

Today’s hymn from Sing Praise (the third in the Ascension Day series) is “Clap your hands all you nations” by John Bell. The tune is brisk and slightly syncopated, which suits the style of an acclamation of praise. The format is of three verses, each verse having four lines with a refrain of “Amen, Alleluia!” after each line. This could lend itself to a cantor-and-response setting, or the whole hymn can easily be picked up by the congregation.

The words are based on Psalm 47, and include in verse 3 of the hymn verse 5 of the psalm, “God has gone up with a shout, the Lord with the sound of a trumpet” (NRSV translation). It is this phrase “God has gone up” that links this psalm with the Ascension. Gerald Finzi wrote an Ascensiontide anthem “Sing praises out”, which includes verses from this psalm and Ps.24 along with lines from Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poetry. I have two recordings of this, a grand one by the Halifax Choral Society and a more intimate one by the smaller choir of Lincoln College, Oxford.

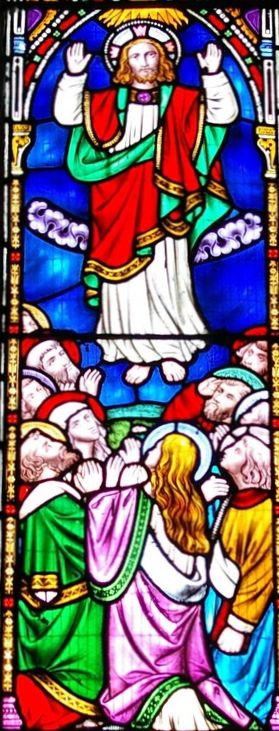

The Biblical account of the Ascension in Luke/Acts (with a brief mention by Mark) does not mention trumpets, in fact the disciples are portrayed as confused rather than triumphant at the spectacle. The trumpets, used in many human societies to herald the arrival of a ruler, are perhaps intended to represent rejoicing in heaven at the successful return of the Son of God from his mission to earth, hence Finzi’s wording that we sing praises to God “seraphicwise” (that is, like the angels).

Meditating on the words of the hymn and the psalm, I was struck by John Bell’s wording of Ps.47:9, “those on earth who are mighty still belong to our maker”. I can see a double meaning here: that God abandons no-one, be they powerful or powerless in society; or that everyone, even if they see themselves as ‘above the law’ on earth, is still accountable to God for their actions. The second perhaps fits the theme of the season better: Jesus may have gone out of sight, but he still knows what we are doing and will one day judge us for it.

We’re out of the Easter season now, so according to my plan no more Saturday hymns until Advent (just because there are fewer than 365 hymns in the book). On Sunday we start looking forward to Pentecost.