All-age talk for Creation Sunday, 4 June 2023, St Peter’s Bramley

(based on Psalm 104 , outline by Julia Wilkins & Tearfund resources)

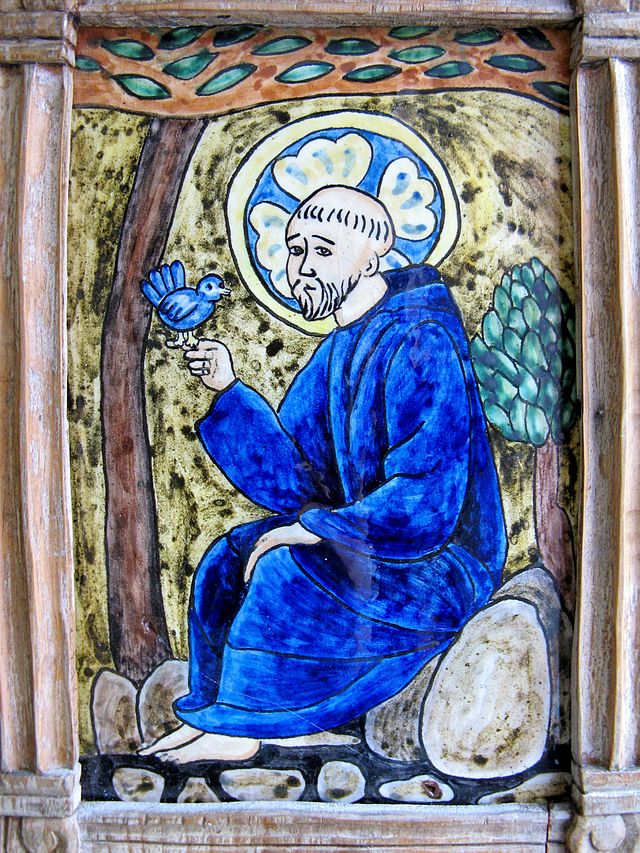

We live in an amazing world! Psalm 24 tells us that ‘The earth is the Lord’s, and everything in it.’ Throughout scripture, we see God’s great love for this world he has created. The Psalm we just said calls it a ‘wildly wonderful world’. Full of the most extraordinary and weird creatures. All the time we’re finding ones that we didn’t know existed! But God knew all along – he knows every single species on this earth, and he made each of them different and special. Everything, from the simplest microbes to the size of the blue whale and the complexity of the human brain, he caused to evolve over millions of years to be just as he wanted. And creation still continues. All the time, plants and animals continue to adapt to their environment. An environment in which every creature, great or small, plays its part.

Once upon a time, everyone lived in villages or small towns. Most people either worked on farms, or at least spent time in the countryside every day, walking from village to village or to their parish church on Sunday – which might have meant walking many miles, even over a hill! In their work and leisure, they would get to watch the seasons change, know when each flower would bloom, each type of tree come into leaf, each type of animal give birth. They could see and feel the weather changing around them, would know which mushrooms and berries were edible and which poisonous. Farmers would fertilise their fields with the dung of their own animals, and the bees that pollinated their crops would produce honey for them to eat. Humans, animals and plants in total harmony, the whole earth one living organism, or as we call it now, the ecosystem.

But as people multiplied, cities grew. More than half the people in the world now live in big cities (and on a world scale, Leeds is not a big city). By 2050 that will be two-thirds. Farming has became a big industry (unless you buy organic food it will have been grown with artificial fertiliser) and many people rarely if ever get the chance to see their food growing or to see animals in their natural environment. Perhaps that’s just inevitable – it’s not realistic for everyone in a city to grow their own food. But it has disconnected us from nature. We can be tempted to think that women, men and children are not part of the ecosystem, somehow above the natural world of plants and animals rather than part of it. How wrong we are!

Beyond simply farming on a large scale to feed more people, the way that modern people live – and that includes us – is harming this ecosystem and putting it under more and more strain. Plants and animals are forced to adapt to changes that are not good for them, or if they can’t adapt they die out. Like Humpty Dumpty, the world is broken and all the King’s horses and all the King’s men cannot put it back together again.

Theologians – that’s people who write about God and the Bible – are increasingly understanding that what the Bible says about Jesus coming to save the world is far more than just forgiving our sins and promising people eternal life. He came to make all of creation whole again, to put this broken world back together. As Jesus was involved in creation from the beginning, only he can heal it.

But he needs us, as his brothers and sisters, to play our part. We have to think hard about how we live and how it damages creation. Tomorrow is World Environment Day. This year the theme is #BeatPlasticPollution. While plastic has many valuable uses, it is mostly made from oil, which is not a renewable resource and contributes to climate change. Our consumer society relies on single-use plastic products, which has consequences not only for the environment but for social and economic structures and people’s health.

For example, can you picture one million plastic bottles? Roughly speaking, that would fill this worship space to head height. That’s how many are purchased every minute around the world. While I’ve been talking, the church would have filled up with just the plastic bottles being used. In five days, they would fill Wembley Stadium.

Each year five trillion plastic bags are used – that’s five million million, nearly a thousand for every person on earth. Yet although most of it could be recycled, half of all plastic produced is designed to be used just once and thrown away. Very little actually gets recycled, even in richer countries like ours. A quarter of the people in the world don’t even have their rubbish collected. Over half of it ends up in landfill, the rest being burnt (which again contributes to climate change), or clogging up the world’s oceans and beaches. Many animals are harmed by our waste, and two people die every minute as a result of human waste, whether that’s toxic fumes from burning plastic or water polluted by chemicals.

Plastic is just one of the many environmental issues that need tackling. But the situation is not hopeless. You may be aware that last week, representatives from 170 countries gathered in Paris and negotiated a first draft of a global treaty to reduce plastic pollution. But it will take years to put into practice, and like all such treaties, will be impossible to enforce. It’s more important that all of us as individuals do what we can to reduce plastic use, and recycle what we can. Here are just a few things you could do:

- Shop at Bramley Wholefoods (Ecotopia) and refill your bottles and jars instead of buying new ones.

- Take cotton or jute bags every time you go shopping, instead of getting plastic ones each time.

- Buy loose vegetables instead of pre-packed ones

- Sign Tearfund’s online petition https://tearfund.org/rubbishpetition

Our reading ended with the words: “The glory of God – let it last forever! Let God enjoy his creation!” Is the way you live allowing God to enjoy his creation, or are you breaking his heart by spoiling it? What changes can you think of that you can make to help restore this wonderfully wild world? What could we do as a church to care more for our local area so that God can enjoy his creation, and how? At St Peter’s we’re planning to form a task force, an action group – whatever you want to call it – to take action together to improve our local environment in any way we can. If you think you could be part of that, please have a word with Julia. In a moment, we’re going to take a few minutes while the worship groups sings, for you to write any pledges on the cards you’ve been given and bring them to the front. But first, let’s pray:

Father, thank you for the opportunity we’ve had today to see our world through your eyes. We pray that as you invite us to change our current ways of living, our identities will be firmly rooted in you and our hearts will be open to consider the ways that we can bring your justice through the way we live. We pray for Christians who are campaigning across the world on plastics, waste and the environment. We pray that decision makers will see the urgency of the issues, that they will be turned towards compassion, and that they will be willing to commit and be held accountable for transforming our society. In Jesus’ name, Amen.

David Attenborough video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iYXBJmrsxZU

Tearfund video: https://vimeo.com/791870984

Closing prayer and other ideas from https://www.tearfund.org/-/media/tearfund/files/campaigns/rubbish-campaign/rubbish-campaign_churchtalk_aw.pdf