For Ash Wednesday, 14th February 2024. Text: John 8:1-11

Picture the scene: we are in the outer courtyard of the Temple in Jerusalem, at the time of the Feast of Booths, around the beginning of October. Jesus is teaching to the appreciative crowds who have come to hear him, but among them are some of Jesus’ opponents who are looking to find more evidence that he has broken Jewish laws.

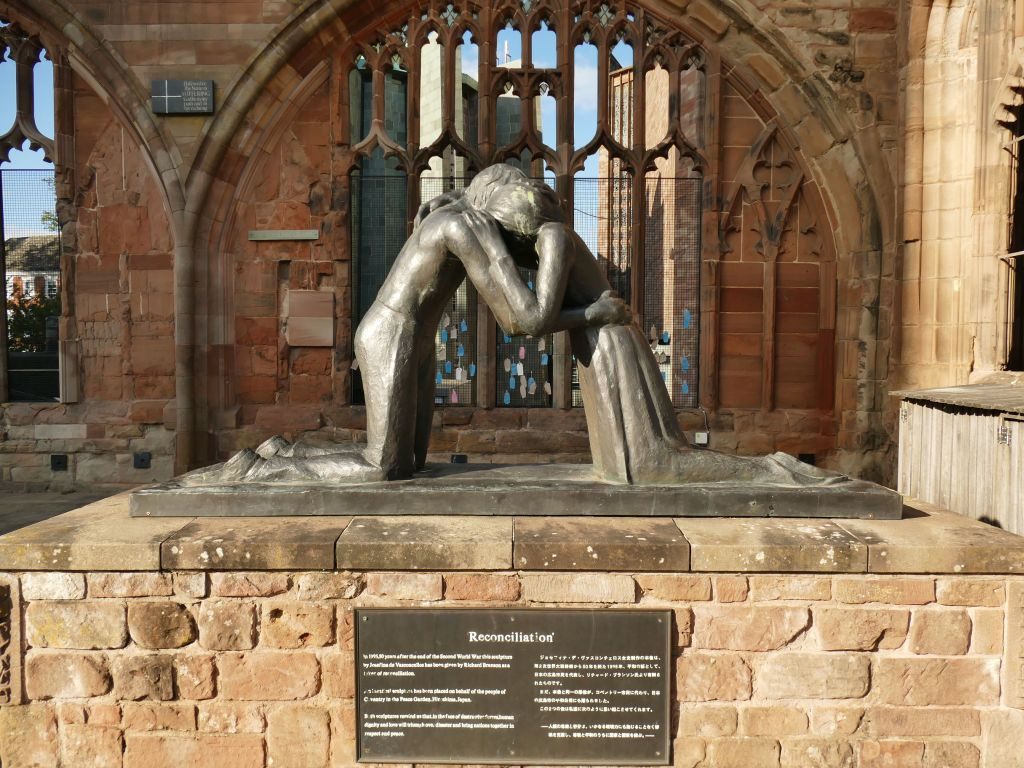

A woman is brought in – unwillingly no doubt, perhaps even kicking and shouting – and dumped on the ground before Jesus, as ‘exhibit A’ in this kangaroo court. Here is someone who has clearly broken the law, the commandment forbidding adultery. Surely Jesus would not fail to judge her and find her guilty? Would he? Well, at the end of the story, while he did not condemn her, neither did he condone her part in the relationship, because he told her to sin no more. After that experience, I’m sure she didn’t.

But despite the title of this passage in most Bibles, this isn’t really about the woman. It’s about the men who brought her to Jesus, using her as a pawn to entrap him. And it’s Jesus’ response to them that I want us to ponder this Lent.

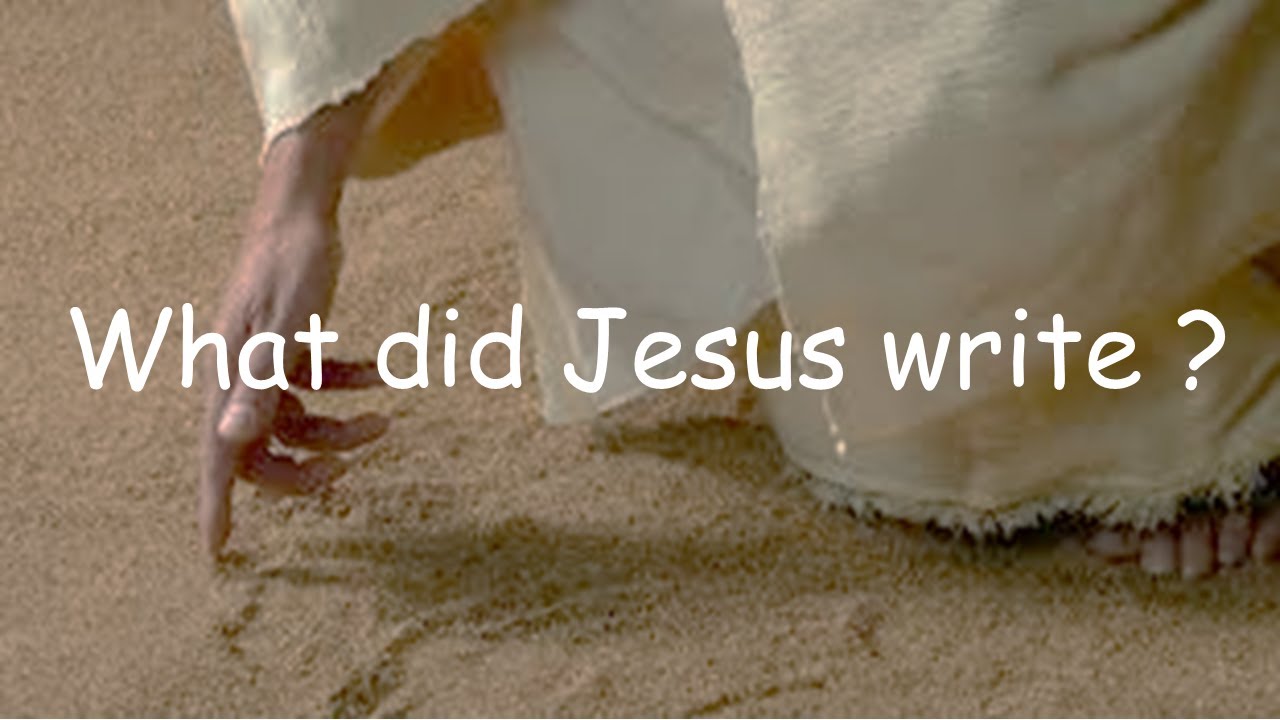

Challenged by them to give his judgement, Jesus doesn’t reply immediately. He lets them put their case for the prosecution before commenting, and as they do so, he writes something in the dust on the ground with his finger. This is one of those bits of the Bible where you really wish the writer had given us a bit more detail. Go on, John, tell us what Jesus wrote! There have been many suggestions over the years. Was it Deuteronomy 22:22, that made the man involved just as deserving of death as his victim? Was it the Sh’ma Y’Israel, the Jewish daily prayer in which believers are reminded to avoid the lust of the heart and eyes?[1] Was it the names of men in the community known to be two-timing their own wives? Was it all the ten commandments, meaning that no-one could claim to have kept all of them? Or maybe the sign of the cross? You can find several sermons on YouTube giving other suggestions, but no-one can be certain.

Whatever he wrote, it had the desired effect when he did speak. And he spoke not to the woman to condemn her, but to her accusers. He challenged anyone without sin to cast the first stone. In the light of Jesus’ writing, none of them dared risk the charge of hypocrisy by pretending to be perfect. Jesus alone had the moral authority to call out the men’s sexism.

Some years ago it was common in the Church to hear the phrase ‘What Would Jesus Do?’ Some people even wore wristbands with that phrase on them. But today the question is, ‘What would Jesus write?’ Maybe you are aware that you have accused someone else of sin – to their face, or just in your heart. If you were to bring them to Jesus, telling him all about their sins and asking him to condmen them, what would he write on the ground with you in mind?

Leaving aside suitable Bible verses, I was reminded of several common English idioms that he might use.

“Those who live in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones”, perhaps? This reminds us that it’s difficult to criticise others without a charge of hypocrisy, as we all have our own failings and the stones that are thrown back may cause a lot more damage to us than we have caused to them.

“Walk a mile in her shoes”, perhaps? We don’t know the background of this act of adultery. Is it more likely in a male-dominated society that the woman seduced her neighbour’s husband, or that he forced himself on her? Was this an ongoing relationship or a one-off incident? And where did it happen that they were observed? It’s frustrating to say the least when other people criticise us for our faults without knowing what lies behind them. Equally, we don’t know the background of someone else’s apparent failings,

“There but for the grace of God go I”[2] are words that wouldn’t really apply to Jesus, but he might well invite us to apply them to ourselves if we are tempted to judge someone else’s behaviour. It can often only take one unforeseen incident or change in circumstances to force someone into poverty or homelessness, for example, and as a result end up shoplifting to survive. Can we really say we wouldn’t do the same in their circumstances?

“To err is human: to forgive, divine”[3]. That reminds us that the person we accuse of sin is, after all, only human like ourselves. We may want to be quick to condemn them for something we know we would not have done ourselves. But even if their sin is different from ours in nature or degree, we are all in the same position of needing God’s forgiveness for something. And the more we know God’s forgiveness in our own lives, the easier it becomes to forgive others.

How about this phrase, a little less well known: “A hundred pounds of sorrow pays not one ounce of debt”. It’s worth noting that the concept of sin has changed several times in religious history. One of the Jewish understandings of sin, was that is is not so much a breaking of rules, as a debt. If I sin against my neighbour, I owe her a debt, which might be repaid in a literal way by making a gift or a payment, by writing an apology, or by making efforts to restore a broken relationship. But if I sin against God, how can I ever repay a debt to him? The proverb is a reminder that repentance is more than saying sorry, it needs a genuine changing of our ways. It also reminds us that God’s forgiveness made posible through Christ’s sacrifice is one that we can never earn.

But I want to draw this reflection to a close with some verses from the letter of James. This apostle, possibly Jesus’ brother, is perhaps best known for his writings about good deeds being as important as faith. But he also wrote this: “For the one who said, ‘You shall not commit adultery’, also said, ‘You shall not murder.’ Now if you do not commit adultery but if you murder, you have become a transgressor of the law. So speak and so act as those who are to be judged by the law of liberty. For judgement will be without mercy to anyone who has shown no mercy; mercy triumphs over judgement”[4].

We all tend to judge others, but this passage about the men who brought a sinner to Jesus, along with many others in the Gospels, shows that Jesus’ approach to the Jewish law was radical. Time after time, he shows that while actual sins need to be acknowledged and repented of, the greatest element in God’s character is his ‘ḥesed’, his loving mercy. If something your neighbour has done or said offends you, before you criticise them openly or pray for them as a sinner, bear this in mind, that if you do not condemn them, neither does Jesus. He knows their sin: it is for him to forgive; it is for you to show mercy, that God’s mercy may be shown to you. Mercy triumphs over judgement.

On me, Lord, have mercy, On me, Christ, have mercy. Amen.

[1] Numbers 15:39

[2] Often attributed to John Bradford (C16) but uncertain.

[3] Alexander Pope, 1711

[4] James 2:11-13