Today’s hymn for Holy Week in Sing Praise is “Jesus, in dark Gethsemane” by Alan Gaunt, set to a surprisingly upbeat English folk tune, given its dark theme. The words of the hymn, though, contrast Jesus’ sufferings with what the Prayer Book calls “the benefits of his Passion”.

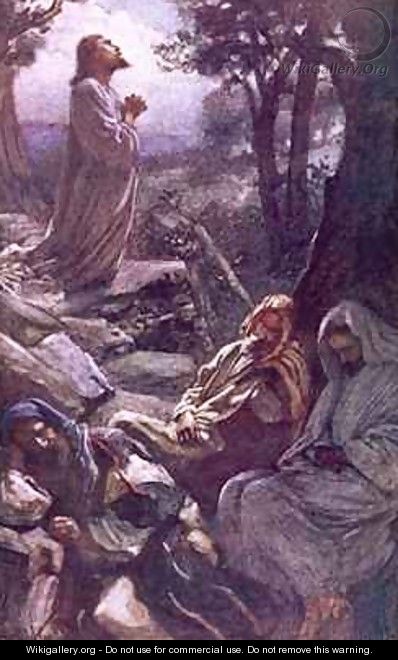

The contrast in verse 1 is between the disciples who could not stay awake while Jesus wept and prayed, and us who ask him to keep us awake. I can empathise with those disciples, as when life is hectic, the brief stillness of a prayer meeting can easily lead to unintended falling asleep. Verse 2 reminds us that Jesus’ prayer “remove this cup from me … yet not what I want but what you want” was answered not with deliverance but with the strength to face death.

Verse 3 is marked as optional, perhaps because its topic of Christ descending into hell is not part of mainstream Christian teaching nowadays. Verse 4 refers to the belief that Christ’s suffering, although it was effective “once for all” in redeeming us from sin, still continues (his risen existence being beyond concepts of time): “faith … knows the anguish love still undergoes to heal our wretchedness”.

Verse 5 refers to the times we must shoulder our own cross, asking for his help to “cling to your nailed hands and, trusting, sing the triumph of your cause”, in other words, to continue praising Christ for what he has done, as a way of receiving his strength in our own troubles. The last verse asks for the Spirit to keep us praising him through both life and death.

To summarise: Jesus, then, suffered agony once upon the cross (and in the events leading up to it) but both his suffering, and his power to relieve ours, remain valid today, as do the forgiveness and reconciliation that it achieved, for Jesus has gone to hell and back, and now reigns as the everlasting Christ.