The hymn from Sing Praise for Trinity Sunday is “Holy, holy, holy one, Love’s eternal Trinity”. There are of course many hymns that begin “Holy, holy, holy” as this threefold acknowledgement of God’s holiness is an ancient form of address to God found in the Jewish scriptures, three being seen as a symbol of perfection. In the Christian church it gets an extra layer of meaning, as we understand God to have three ‘persons’ or ‘manifestations’ as Father/creator, Son/Word/redeemer, and Holy Spirit/advocate/comforter.

This particular hymn is by Alan Gaunt. It has five verses and follows a pattern common in other such hymns of having the first and last verses addressed to the Trinity, and each of the others focussing on one of the persons. So God is described variously as “Holy source of all that lives” (creator), “Holy Lamb, love’s sacrifice” (redeemer) and “Holy Spirit, deathless joy”.

What binds the verses together, apart from the “Holy” titles is the last line of each verse: “here I am, my God, send me”. Encountering the holiness of God should result in a response of wanting to serve him. The different verses suggest differing responses as we encounter the persons of the Trinity. With the Creator, “through creation’s mystery your love speaks and we reply…”. With the Redeemer who gave his life for us, “mighty in humility, overawed we humbly say…”. With the Spirit, the one who inspires witness, “though we face Love’s agony, touch our lips and we will cry…”. And in the last verse, to the three-in-one we say “call our name and we will be each Love’s living sacrifice: here I am, my God, send me”.

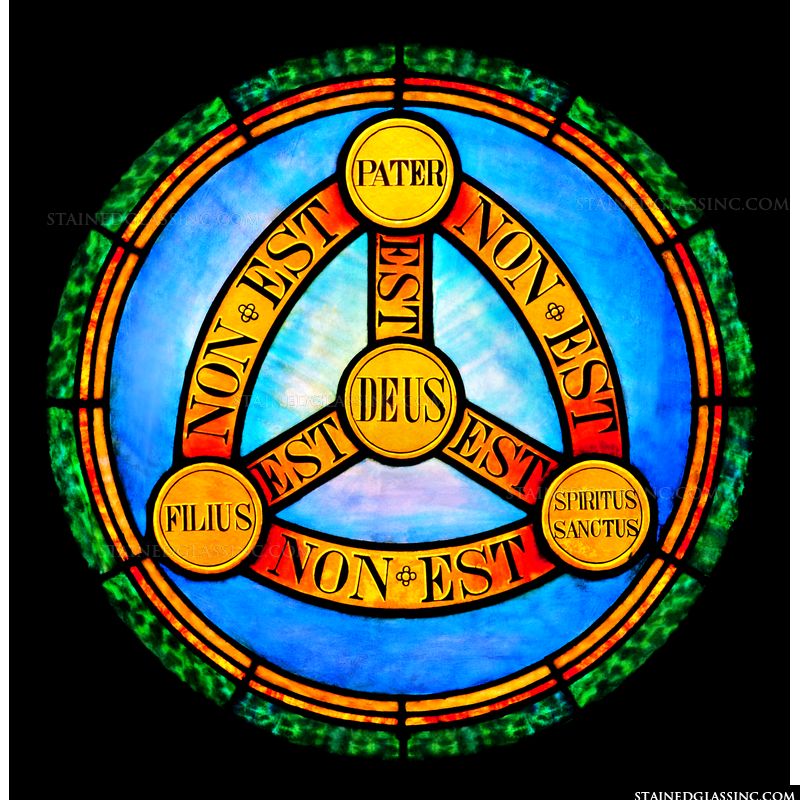

The Trinity cannot be explained, and indeed some churches don’t attempt to, preferring a Unitarian position. But for most of us, it’s worth trying to understand that the unseeable force behind creation, the man Jesus who was raised from the dead and taken into heaven, and the unseen but often experienced spiritual power, are one and the same God who wants to send us to call others into his presence.

Through the first half of the Church’s year from Advent to Trinity we have studied the promises of God from ancient times, the birth, life, death, resurrection and ascension of Jesus and the coming of the Spirit. Now as we put all that together we have the second half of the year, from now until the end of November, to put it into practice. “Ordinary time” it may be called in the calendar, but if we have encountered God, it should be far from ordinary.

I have a soft spot for Alan Gaunt, having met him several times at the Hymn Society of Great Britain and Ireland’s conferences – he is a sensitive poet and a caring man, and I immediately warmed to these words which take their inspiration from Isaiah 6 (with its vision of “Holy, holy, holy” and its response of “here I am, send me”). This chapter of Isaiah was interpreted by early Christians as Trinitarian because of the repetition of the word “holy” three times, and this hymn fleshes this out with opening and closing verses to the Trinity, around three to the individual Persons which each take up some aspect of that Person’s ministries. I also liked the personification of “Love” in the hymn, which emphasises the poetic and allusive quality of the writing, as well as rooting the Trinity in the internal relationships of the Godhead. I think the one phrase I did query was “Deathless Joy” as an alternative description of the Holy Spirit.

In the book the suggested tune is a fairly standard 7.7.7.7 “Randolph” by Ralph Vaughan-Williams, but I felt the words needed something with a distinctive rhythm in its final line – so I wrote one, and sung it to that. (And I sent the tune to Alan, who was gracious enough to reply saying he liked it.)

* * * * *

Stephen says “the Trinity cannot be explained” – but I think the point of the “doctrine of the Trinity” is that it tries to draw a boundary between the ways that words can and cannot be used to make statements about the relationships between the words “God”, “Father”, “Son”, “Jesus”, “Holy Spirit” as they are used in the scriptures. The passage in Sheldon Vanauken’s book “A severe mercy” (in which he asks what happens when an author writes a book in which he also appears as a character) is particularly helpful. And, of course, in modern-day Quantum Mechanics, the ways we use words like “particle” and “wave” and “interactions” and “probabilities” and so on, to describe what is actually going on with photons and electrons and other such “objects” – these show how the right and wrong use of words is critical for reaching a proper understanding and descriptions which enables us to make meaningful deductions. But I must stop – I feel a sermon coming on!