From http://davidgospeldaily.blogspot.com/

(original artist unknown)

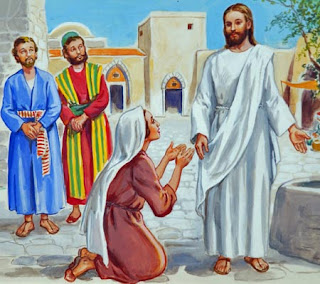

Today’s hymn from Sing Praise is ‘The servant King’ by Graham Kendrick. It’s not normally thought of as a Christmas hymn, as it focuses on the death rather than the birth of Jesus, but John suggested it for today and with good reason. The Gospel reading at morning prayer today was from Matthew chapter 20 and concluded with these words of Jesus to his disciples: “Whoever wishes to be great among you must be your servant, and whoever wishes to be first among you must be your slave, just as the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve and to give his life a ransom for many”. The artwork above illustrates the Biblical context of this saying, with the mother of two of the disciples asking for them to be his chief assistants.

That phrase ‘not to be served but to serve’ appears in the first verse of Kendrick’s hymn, reminding us that the ‘helpless babe’ we put in nativity scenes at Christmas would go on to live a totally selfless life and offer himself up to cruel death for our sake, as the rest of the hymn makes clear.

The final verse turns back on ourselves: it’s one thing to give thanks to God for Jesus’ willingness to die for us, but are we prepared to offer our own lives as servants, both of Jesus and of each other? Christmas, supposedly a joyous festival of the birth of our Saviour, is notorious also as a time when domestic quarrels can escalate into violence, and strained partnerships tear apart. So may the promise “each other’s needs to prefer” sustain our homes in peace through this season.