A sermon for Maundy Thursday at St Peter’s Bramley

Readings: Exodus 12:1-14 / John 13:1-35

Have you ever found yourself in a situation where you didn’t understand what was going on? I recall at least two such occasions, one secular and one spiritual.

A couple of years ago, my manager invited me to a meeting. I was given only a vague idea of what it was about and didn’t know who else would be present. I entered the room to find my manager talking to two people I didn’t know. I took my seat and the conversation continued without reference to me. Eventually I could stand it no longer and I interrupted, to ask if we could have some introductions, and some context for the conversation so that I could understand the discussion and join in. Afterwards my manager apologised, and agreed that there should have been introductions and an agenda.

Back in the 1990s, as those who have been Christians a long time ago may recall, there was a worldwide spiritual revival called the Toronto Blessing. Some members of my congregation had been to the New Wine Christian festival that year, and when they returned to the local church, several of them had changed in what seemed to me very odd ways. One young woman who was normally very shy and quiet had become much more confident in her faith and told of how the Holy Spirit had physically thrown her across the room. One older lady found that whenever the Bible was read aloud, she would shake uncontrollably. Others had received the gift of tongues for the first time. I’m not doubting that any of these experiences were genuine for those concerned, but to me it was disconcerting, and if I’m honest a bit frightening.

Both our readings today, as we remember Jesus’ last supper with his disciples before the crucifixion, are about people confused and frightened by spiritual goings-on. Put yourself in the position of the Israelite people: not Moses and Aaron, but the ordinary folk: the shepherds, brickmakers, straw-gatherers, male and female slaves, children in the street. They had experienced a series of plagues the like of which no-one had seen before: frogs, gnats, locusts, hail… it must have been truly terrifying. And now they are told what they must do to avoid their eldest sons being killed by the angel of death: they were to kill a lamb, spread its blood around the door, roast and eat it – but not with the usual vegetables, instead with bitter herbs and unleavened bread. And to dress for the occasion: not in their best clothes, but in belted tunic and sandals, holding a staff. The outfit of a pilgrim. And to eat the meat in haste, because as soon as the meal was over, they would have to flee for their lives.

Did the people act on these strange instructions? It seems they did, as the Exodus story givens no hint of any of them being left behind. In confusion they followed Moses and Aaron across the plains to the Red Sea, and we all know what happened next.

Move forward perhaps thirteen hundred years. Jesus’ disciples had already seen many miracles and other odd happenings over the last few years with Jesus, and other events more recently may not have made much sense, such as Jesus’ riding into Jerusalem on a donkey. But now they had been sent ahead to prepare the Upper Room for the Passover meal. At least they knew what to expect this time. There was a set menu, and the story of the Exodus was repeated word for word every year.

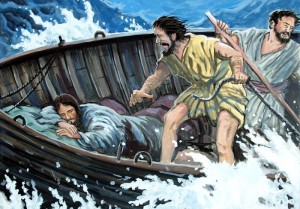

Except, this time it wasn’t. Jesus, their Lord and Messiah, acted like a slave in washing their feet. He used the occasion to warn of his imminent betrayal and death. Judas left the room to go about some unspecified business, which Jesus understood but the rest didn’t. Jesus started talking about his body and blood instead of bread and wine. And then, like the people of Israel in Egypt, as soon as the meal was ended they were ushered out into the darkness on a journey to – what? Very, very, strange. But again, there’s no suggestion that anyone was left behind. Without understanding, but with complete trust in Jesus, they followed on to find out what happened next.

What is it that makes people join in and follow without fully understanding what’s going on? In a word, faith. In our Start course sessions during Lent, we have discussed how much we need to understand about the Bible and the Christian life to set out on a journey of faith. The answer seems to be, not very much. If we can grasp the essentials, the rest will follow in good time. And there’s good precedent for this: the 11th century theologian Anslem of Canterbury is perhaps best known for his three-word summary of Christian theology as being ‘Faith seeking understanding’. Faith comes first; understanding follows.

But what is this faith that we can grasp, before fully understanding it? The connection between the Exodus and Holy Week is no coincidence. In God’s master plan, one was always intended as a shadow, a prequel if you like, for the other. The details may have been different, but the core message was the same. I suggest it can be reduced, like Anselm’s summary of theology, to three words:

Lamb, blood, salvation.

The descendants of Jacob who ended up in Egypt were pastoral nomads. Lambs would be slaughtered as a sacrifice to God, and the meat would have been a regular part of their diet. But in this special feast it took on a new significance. The blood of the lamb, in particular, was used in this new ritual of marking the doors for protection against death. And through this Exodus, this going out from the plague-stricken land of Egypt, not only would their firstborn be saved from imminent death, but the whole of the twelve tribes would be saved from the wrath of Pharaoh. They didn’t understand at the time what was happening, but later they did, and passed the story down the generations until Jesus took it up that Passover eve in Jerusalem.

What Jesus did on Good Friday was to take this story of salvation through the blood of the lamb and make it his own. Not without reason did John the Baptist call Jesus the Lamb of God: it’s a title that has come down through the centuries. In his one, perfect sacrifice for sin, Jesus did away with the need for any other kind of sacrifice, whether of lambs or anything else. By inviting his disciples, and all who would follow, to share the cup of wine in remembrance of the shedding of his blood, we are united with each other and with those who came before us in the story of salvation. In his death, through the shedding of innocent blood, and through his resurrection that echoes the people if Israel coming up out of the waters of the Red Sea, Jesus has led us out from the slavery of sin, into the freedom of a life with God, without the fear of his wrath.

Those disciples didn’t understand, in the Upper Room, what all this was about. Later, after the Resurrection, Ascension and Pentecost, they did, the Gospel was preached, then written and passed down the centuries to us.

Now, it is for you and me to take this story and make it our own. To have faith in our Saviour, faith that throughout our life seeks a deeper understanding. To pass it on to new generations, that they too may know, believe and understand. This is his story: this is our song.

Lamb, blood, salvation.

Amen.