Found at https://www.freedomfrommedom.com/ – original artist unknown

Today’s hymn from Sing Praise is the first of two on consecutive days by the Scottish hymnwriters John Bell & Graham Maule, both in the series on social justice issues. Both of them invite us to join our own concerns with those of God. This one, “Inspired by love and anger”, puts words into the mouths of various groups before turning to God himself. The full words can be found here.The tune, Salley Gardens, is a gentle Irish folk melody, easily memorised, but perhaps a little too gentle for the subject matter

Verse 1 invites us to be “inspired by love and anger, disturbed by need and pain”. It’s all too easy to suffer compassion fatigue as we hear of yet more suffering in the world (just this week, uncountable Covid cases in India and two localised disasters in Israel and Mexico, for example). “How long can few folk mind?” may well be a question aimed at ourselves.

Verses 2 and 3 offer a contrast between the cries of the victims for justice, peace, and release of prisoners; and the rich who ask not to be criticised for their position, wealth and exploitation of others. To be fair, not all rich people are like that: Bill Gates is said the be the fourth richest person in the world with assets exceeding $100 billion, but he and Melinda are also great philanthropists who do genuinely seem to seek fairness in the world.

In verse 4 we offer up to God the “agony and rage” of Earth and ask when his kingdom of equity will come. In verse 5, God responds by asking, as he did through Isaiah, “Who will go for me, who will extend my reach, and who when few will listen will prophesy and preach?” A common response to that question is “Is it I, Lord?”. This is prayer as dialogue leading to action.

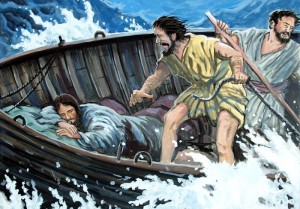

The last verse turns to Jesus, using some imaginative wording. He is pictured “amused in someone’s kitchen, asleep in someone’s boat” as examples of being with us in ordinary life. His ministry is summed up as being “a saviour without safety, a tradesman without tools”. It’s not a very satisfactory ending, as it doesn’t really explain how God in Jesus – or in us – does answer the earth’s call for justice. We need more guidance from this sleeping saviour on how exactly we are to work with him in this way.