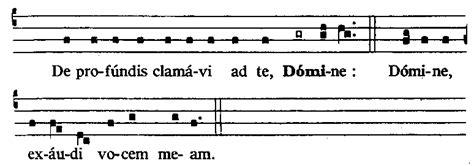

Today’s hymn from “Sing Praise” is “O God, be gracious to me in your love”, a setting of Psalm 51 by Ian Pitt-Watson using a tune by the 17th century composer Orlando Gibbons.

Psalm 51 as a piece of music is best known in Allegri’s setting of the Latin text known by its first word “Miserere”. It’s a favourite choice as a “romantic” piece of music, which is rather ironic. The words are a confession of a serious sin, the nature of which is not specified, and a commentary I consulted suggests that it was probably written after the Exile rather than before (as evidenced by the last two verses about sacrifices in the Temple), but it’s traditionally associated with King David being confronted about his adultery with Bathsheba as recounted in 2 Samuel chapters 11-12. ‘Adultery’ is itself something of a euphemism here, as she wasn’t in a position to refuse his advances, and that sin was compounded by the arranged killing of her husband when the king found he had got her pregnant.

The words as set here are quite a close rendering of other English translations of the psalm, with a regular metre (I believe iambic pentameter, but I stand to be corrected by literary experts) without attempting to force rhymes. It could therefore be used quite easily as a said version of the psalm rather than as a song, and the theme of confession does of course fit well with the discipline of Lent. What can we learn from it?

The line that stands out for me is “Against you, Lord, you only have I sinned”. This sounds as if I (or David or whoever wrote the psalm) have not actually sinned against anyone else, which seems to fly in the face of experience: while some ‘sins’ may technically be only against God (such as pride, for example) others such as taking your neighbour’s wife as your own and having her husband murdered are obviously offences against those people and those close to them. What might this mean? As one commentary puts it, “sin is ultimately a religious concept rather than an ethical one” – breaking human laws relating to marriage and killing (or any other law) can be dealt with by secular courts, but sin at its heart is falling short of what God expects of us as humans “made in his image”, that is to live in harmony with other people and with nature, and for that we are answerable to a higher authority. And admitting guilt in court is not the same as admitting to God that I am a broken person needing his mercy. If this is David’s story, as King he was probably above the secular law anyway, and it was only when the prophet Nathan turned the facts into a parable about a pet lamb that David’s defences broke down and he showed contrition.

The other point is that for confession to be meaningful there must be a genuine desire both to be forgiven and to change – “wash me and make me whiter than the snow” … “create a clean and contrite heart in me”, to use the translation given here. The final verse of the hymn includes lines that are used at Evensong in the church of England: “O God, make clean our hearts within us, and take not thy Holy Spirit from us.” “Heart” in the Bible tends to refer to the will or desire, rather than emotions, so this is about asking the Spirit to give us right intentions.