Today’s hymn from Sing Praise is a very well known one, “O Lord my God, when I in awesome wonder”. Stuart Hine’s translation of a hymn that was originally either in Swedish or Russian (I’ve seen both quoted as the original) has become a firm favourite, at least partly because of the memorable tune (although the two slightly different notes on the repetition of ‘art’ in the chorus catch many out).

I do wonder, though, whether its popularity is also because the first two verses appeal to a spirituality of nature that doesn’t demand Christian commitment. Stars, woods and glades, brooks and birds can be enjoyed by anyone, and only a vague belief in a creator is required to respond to them with “how great thou art!”

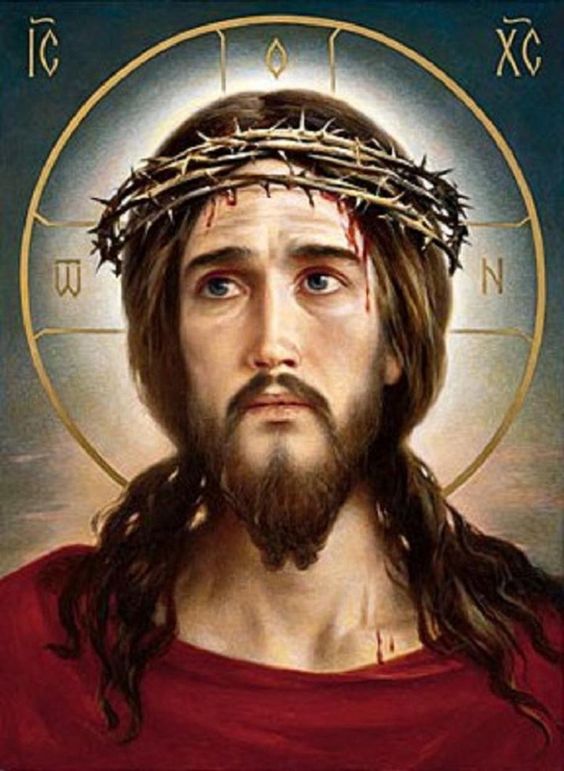

The last two verses, on the other hand, if the singer thinks about the words, are much more specifically Christian. “When I think that God, his son not sparing, sent him to die … on the cross, my burden gladly bearing, he bled and died to take away my sin” is at the core of our belief, and all the more reason to be thankful to our God. He is not a distant creator far beyond the stars, but among us and involved with us in sharing our suffering.

The last verse looks to the renewed creation promised by Jesus, which shall be our home. Interpretations of Christ’s return do of course vary between Christians, but we can agree that the greatest gift of God for which we can sing our thankful praise is that of eternal life, whether in the present existence or the one to come (whatever that may be like). How great thou art, indeed!