If this is your first visit, please see my introduction to these Lenten readings.

30 March 2018. Daniel chapter 14

Like the story of Susannah on which I wrote earlier this week, this chapter, known as “Bel and the dragon”, is unrelated to the rest of the book of Daniel and is only included because Daniel features in the three short stories that it comprises, all of which share the theme of the defeat of idolatry. The chapter is omitted in Protestant Bibles as “apocryphal”.

In the first of the short stories, King Cyrus – mentioned elsewhere in the Bible and undoubtedly a historical person – is portrayed as worshiping the idol called Bel or Marduk which appears to eat a large amount of food (including sacrificed sheep). Daniel is no under illusion – he knows that the idol is only a bronze -covered clay statue, and tells the king that their must be trickery. Cyrus is at least willing to investigate the truth, but the priests of Bel are confident their secret trap door (by which they go in to eat the idol’s food at night) will not be discovered. Daniel uses a simple built of forensic investigation by scattering ashes on the floor to expose the footprints of the people who come in at night, and thus persuades the king to stop worshiping the idol.

In the second story, the king is now worshiping a living creature – a “dragon” (we cannot know what sort of animal this really was). He believes it to be immortal, but Daniel very simply chokes it to death with balls of hair, grease and pitch. In this way he persuades the king to drop the practice of idolatry. But that is not the end of the story – for the second time (if the stories in the book are in chronological order) Daniel is fed to the lions, yet survives by God’s miraculous intervention.

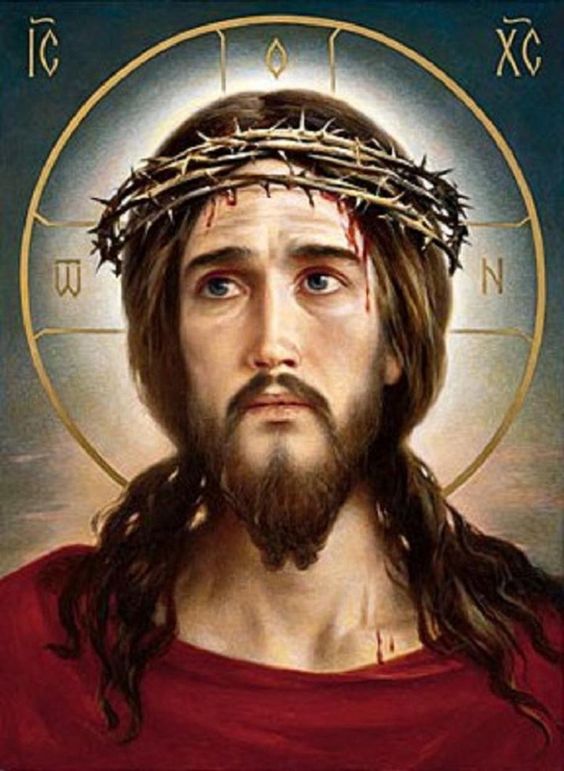

Is there any relevance to this story for Christians? Yes, very much so! Today is Good Friday, when Jesus was condemned to death by Pontius Pilate. Pilate found himself in the same position as Cyrus did – faced with a believer in God who had been upsetting the religious systems of their day, yet willing to be persuaded that the believer in question was not only harmless to society, but maybe even right in representing a different form of religion.

Yet in both cases, the priests of the established religion – the servants of Bel, or the priests of the Jerusalem temple who professed to worship the true God, the God of Abraham (and for that matter Daniel) – were so afraid of losing their influence and their income that they threatened to riot. Just as the priests of Bel “pressed [Cyrus] so hard that the king found himself forced to hand Daniel over to them to throw Daniel into the lion pit” (14:30-31), so Pilate was pressed so hard by the Jews to release Barabbas and crucify Jesus, that he did the same.

What can we learn from these stories – true or not? It seems impossible to modern people that an intelligent person such a Cyrus could believe in a statue actually being a god, but then it seems impossible for many people that an intelligent person can believe in an unseen god. The deity of Bel and the Dragon could be disproven; the existence of God can neither be disproven, nor proved by scientific experiment. Daniel, if these stories are true (and the Bible has many examples of people being miraculously preserved from death) could point to the evidence in his life of a saving power, and so can many people today. Belief in God requires faith, but a faith for which there is evidence.

It is not surprising that when Jesus hung on the cross, he was taunted to save himself and come down from the cross. He had healed people of all kinds of illness and disability, even raised people from the dead. But it appeared he could not save himself. Where was the God who rescued Daniel from the lions, Joseph from the pit in which his brothers had thrown him, or the three young men of chapter 3 from the furnace, when his own son was dying? The miracle of Good Friday is in fact in the fact that Jesus was not saved from physical death. For he had to undergo it in order to be raised to life, without which his saving work for all of humanity would not be complete. Daniel’s life was saved as a reward for defeating the power of idolatry and destroying the terrifying dragon, but Jesus on the cross faced down the greater enemy, the unseen power of the Devil. He paid the price for that with his life, but was rewarded with the everlasting life that he also offers to us.

Happy Easter!

Here ends the book of Daniel, and with it my survey of the whole Bible (including the apocryphal bits) over the last 15 months.