The last in this block of specifically Good Friday hymns is another modern one, “This is your coronation” by Sylvia Dunstan. The suggested tune, however, is Bach’s Passion Chorale (actually an older tune than Bach, but his use of it in his passion oratorios ensured its lasting fame and association with Good Friday).

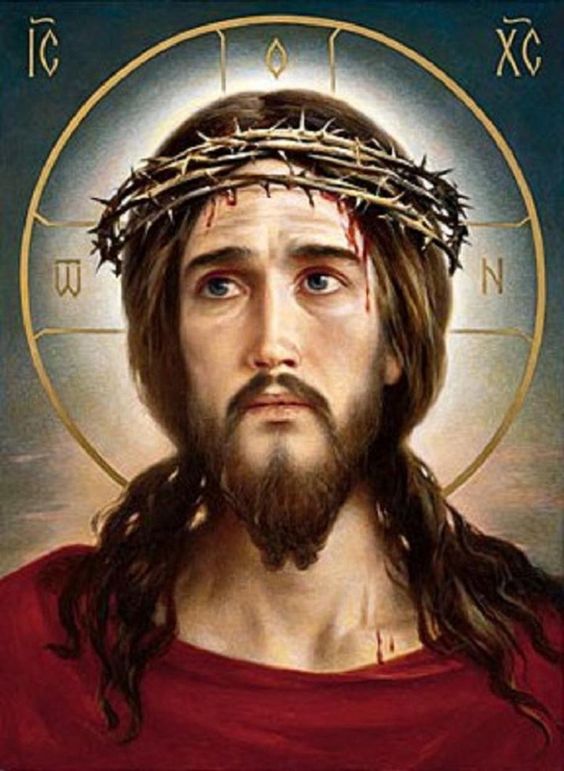

The theme of the Crucifixion is the same as yesterday’s, and some of the same ideas are there: the cross of wood, Jesus’ physical suffering, the blood on his face, his death as a sacrifice, the pardon for our sins that he achieved. But the tone is so different: the tune is sorrowful rather than triumphant, Jesus is presented less as bearing the Father’s wrath towards humanity, and more the willing actor in this cosmic drama.

The three verses each look at one of the traditional images of Jesus Christ: King (verse 1, “this is your coronation”), Judge (verse 2, “Eternal judge on trial”) and High Priest (verse 3). The cross is portrayed as the king’s “throne of timber” (a lovely image), the judge who is condemned by humanity still acts with love to pardon us, and the priest offers himself as the final sacrifice. These three images mirror to some extent those of the gifts of the Magi at Epiphany: gold for a king, incense for a priest and myrrh for a sacrifice.

Altogether this seems a more satisfactory hymn to sing on Good Friday than Townend’s offering yesterday.